By Jay Innis Murray

One of the things that seems to me to be artificial about most fiction is that it pretends as if experience and thought and perception are linear and singular and that we’re thinking and feeling only one way at a certain point in time. You know, some of that is the constraint of the page, and I think to an extent the footnotes are to suggest at least a kind of doubling that I think is a little more realistic.

David Foster Wallace in interview

The other thing that’s useful for me is this notion of the absolute versus the relative. If we walk out and it’s a beautiful morning, it’s only a beautiful morning because we don’t have a broken leg or hemorrhoids or something.

George Saunders in interview

The Delegation is many things at once: a comic epic in prose, a historical novel that meets many of the criteria of Lukács’ classic study, a work of Jewish autofiction (or a hybrid form that looks like it), and, above all, a relentless dissection of the motives and feelings of a man suffering from an acute, physical humiliation. That Avner Landes could pull off all of these in one book is astonishing. This is one of the best novels I have read this year.

On July 8, 1943, more than 45,000 New Yorkers attended a rally at the Polo Grounds in support of the Russian war effort against the Nazis. The two main characters in Landes’ excellent new novel, poet Itzik Feffer and actor/director Solomon Mikhoels, traveled extensively in the USA and elsewhere to raise funds for Stalin’s war effort. The Polo Grounds rally where they both spoke (along with Fiorello LaGuardia, Paul Robeson and other major public figures) is the capping event in the novel’s comic odyssey. Landes brings to life, in fictional form, his imagining of what that odyssey might have been like for these two Jewish men stuck, as they were, walking an unmapped minefield under the nervous eye of Joseph Stalin where the one wrong, complaining word or the lack of comradely enthusiasm could lead to murder by the Soviet security forces.

I adore the story of Feffer, as told here. Before I get into the parts I loved most, here are a few words about the novel’s form. You notice right away, on Page 1, that the novel proceeds in three parts, physically divided on the page. Landes makes it visibly obvious that the historical novel runs along the top half of most pages. A black line, the width of the justified paragraphs, fences off the two bottom parts. These are the “Note from the Author, Izzy Shenkenberg,” which comprises the middle section of each page and the numbered footnotes to Shenkenberg’s Note, which occupy the bottom of each page. I found it took me about 15 pages to adjust and find the way to deal with this design. The writing flows in Landes’ clear, witty style, but the trick is to decide how you’ll tackle the work of reading all the sections. You could presumably read each one all the way through, or skip the Note from the Author, or skip the footnotes. You could come back to the footnotes. You could read all the text on each page before turning it. Lots of options. I found the richest experience for myself was reading a chunk of the historical novel, but not so many pages as to lose my place in the Note from the Author and then read the footnotes as they came up. Again, after about 15 pages, I found this strategy pretty natural and easy.

I can only imagine writing a story like this in the 2020s brings with it certain writerly anxieties about devotion to accuracy, about the writer’s obligations to the history of mass death and/or public figures, and about how it might fit in the history of Jewish literature. A writer could literally be of two minds about it. As with the Wallace quote above, there is a doubling (or tripling) that comes with Landes’ chosen form. It allows a “meta” or hybrid or autofictional voice to storm in as Izzy Shenkenberg tells of writing it, what his sources were, what his writing life was like, what contemporary Yiddish lit was like, along with stories in the lives of people like Paul Robeson, fascinating in themselves but unfit for the top section of this book. It’s a daring choice, and Landes pulls it off.

With all of that said about form, I won’t reveal who the narrator of the historical section is. It is a delightful reveal, and I don’t want to spoil it.

Feffer and Mikhoels have been sent on a difficult errand. They are minor historical figures (Mikhoels was more famous than Feffer, but neither was a figure like Einstein or Stalin). In 1943, Stalin was locked in the massive Eastern front war with Nazi Germany. It was obviously the darkest time for European Jews, as the Final Solution was underway. Feffer and Mikhoels have been sent on a tour to meet with prominent American Jews with the goal of raising donations from them and, as Stalin points out in the novel, to influence the influential: “Feffer and Mikhoels were told by Stalin that the Jews of Western countries wielded major influence over their governments’ decision-making apparatuses, which is why it was important to remind Jews they would meet on their travels that only one country was standing up to the barbaric, fascist Nazis slaughtering their co-nationalists” (Page 30). If American Jews were not as aware as Europeans of the Nazi machinations, they were finding out as family members and friends in home cities and villages in Eastern Europe could not be contacted.

The great heart of this novel is the portrait of Feffer’s unending distress at the difficulties of the journey. He is constantly beset by the pain and itchiness of hemorrhoids. He worries non-stop about the embarrassing smell and leakage of the same. At times, he avoids eating since he knows how digestion will harrow him. He has to think like a frantic kleptomaniac about how he might steal time alone in a bathroom to wipe himself. It has been a long time since I’ve felt such sympathetic vicarious humiliation for a character in a novel. It’s a sort of magic trick that I greatly admire.

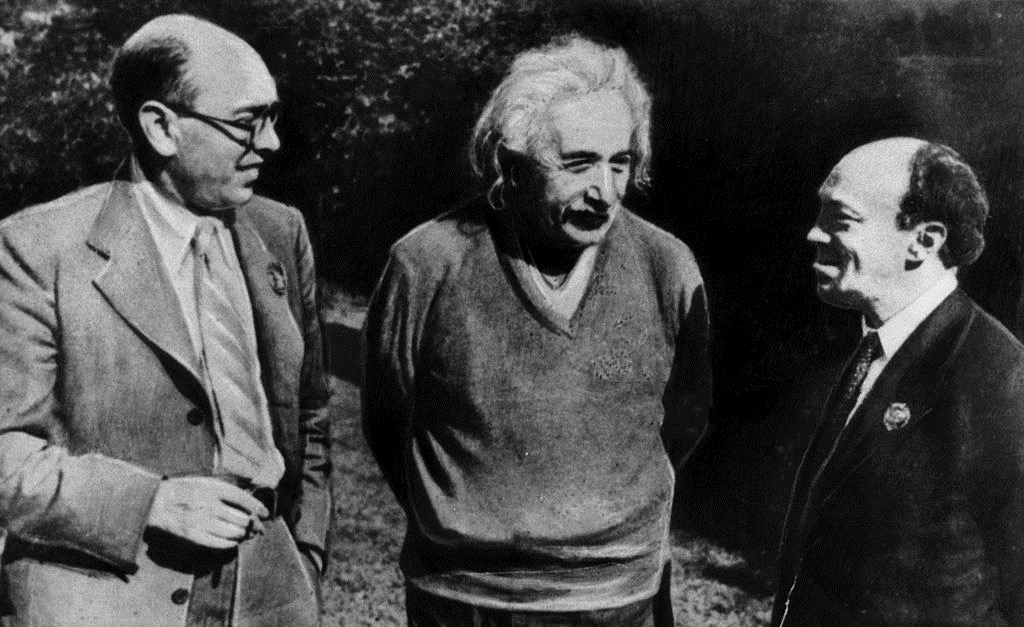

The visit with Einstein is my favorite section of the book. I’ll write about it to give you a good feeling about how the book works and how funny it is. There are important supporting characters I have not yet mentioned. These include Goldberg, their American liaison who leads Feffer and Mikhoels around the US on their tour and Goldye, the woman driver who sexually interests both of the Russian men. Goldberg and Goldye take the two heroes to Einstein’s house and remain in the car. Feffer and Mikhoels encounter a wildly uninhibited Einstein who is hilarious in his frankness. He’s playing the violin in his back yard when they arrive. There is awkwardness when they walk up and expect to be greeted, but Einstein does not stop playing. Here is how Landes describes the scene:

Feffer felt stuck, never a good feeling, especially when dealing with stomach issues, especially with his underwear sticking and giving off a weak but noxious odor. On top of all this, Albert Einstein stood shirtless in front of the men, which added to Feffer’s uneasiness. In the father of relativity’s bulbously sagging breasts and stomach, Feffer saw the face of a frenzied elephant. (Page 214-215).

I laughed hard at that introduction. Einstein, of course, made a recent, heralded appearance in the film Oppenheimer, but he hadn’t looked anything like this Einstein. Nor had the professor sounded like this:

“Poor Elsa was quite sick by this point. Heart problems. Pissing blood,” Einstein continued. “I imagine neither one of you has yet experienced sex with a dying woman. One of the most sensual experiences of my life…” (Page 225)

A daring portrait here, but very human. It pays off as Landes has set the expectation here that anything can happen. The conversation continues, and Feffer finds an opportunity to sneak off to the bathroom inside the house. He is horrified by what he finds in his pants.

A bloody, brown streak, damp and heavy, bisected his underwear, as its odor, which had been following him around the entire day, rose to his nose. Wipe after wipe could not produce a clean sheet, and Feffer fretted over how he’d get through the remainder of the day with long car rides and outdoor affairs ahead of them. (Page 232)

Feffer is left with a dilemma. Suffer with a wad of paper or find replacement underwear. He doesn’t have any, but Einstein and the woman living with him, Margarita, does.

Now: what to do with the underwear and could he find a replacement pair?

The first thought was to stash the soiled pair between the towels, which were stacked in a narrow cabinet in the bathroom’s corner. But a wooden chest in front of the claw-foot tub caught his eye. Inside were dirty clothes, mostly underthings, both his and hers. From the five pairs of underwear—three belonging to Einstein, two to Margarita—he surmised that neither was a fellow sufferer. Her stains were of a different sort and without any smell. He pondered purloining one of the pairs. Einstein’s waist was larger than Feffer’s, and he’d have to fold over the band if he wanted to wear them; her pants tightly gripped his groin, and though the silk did feel nice against his skin, he worried about the tightness exacerbating his intermittent need to shit. Because he was running low, he pulled on a pair of Einstein’s as well, figuring that doubling up would put his mind at ease. (Pages 232-233)

If you’ve never been this desperate, you might find the prose gross, but I think we have here the funniest section of pages in any new novel I’ve read this year. The book isn’t all laughter. In fact, the ultimate fates of the two Russian travelers are quite distressing (think Lavrentiy Beria), but there is such human warmth and observation here. A great novel.

Leave a comment