By Jay Innis Murray

On Bloomsday in 1963, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space, launching in capsule Vostok 6. She orbited the Earth 48 times before landing successfully. Her call sign was Seagull. From space, she radioed to Soviet mission control, “It is I, Seagull! Everything is fine. I see the horizon; it’s a sky blue with a dark strip. How beautiful the Earth is. Everything is going well.” On Bloomsday in 2012, Liu Yang became the first Chinese woman in space. Before she blasted off in the craft Shenzhou 9, Liu Yang said, “When I was a pilot I flew in the sky; now as an astronaut, I’m going into space. It’s higher and it’s farther. I want to feel the unique environment in space and admire the views. I want to explore a beautiful Earth, a beautiful home.”

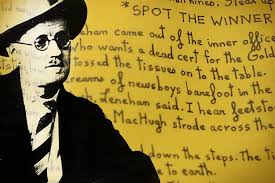

Lee Klein’s wise and funny new novel, Like It Matters, takes place on a single day, that latter, high-flying Bloomsday of June 16, 2012. It’s set in Philadelphia where the Rosenbach Museum and Library (home to James Joyce’s handwritten manuscript of Ulysses) hosts one of America’s biggest annual celebrations of world literature’s consecrated holy day. I’m as hostile as ever to plot spoilers, so I will only say I’ve opened with the bits about astronauts, because Klein has structured this book with the care of an expert screenwriter, so that, while it may seem plotless (writers sitting in a bar drinking craft beers, talking about writing), it has a build and seductive momentum that pulls the reader along to a last act that contains a launch (no other word for it) like something from the wild US fictions of the 1960s and 1970s. I loved every minute of it.

Who are the good-natured writers? Pynchon is the first name that comes to mind. Next, for me, would be Kafka. Let’s add Throop Roebling to this list. He is Klein’s first-person narrator, a knight of the faith of literature. My first impression was that Throop might be a polemicist, a worry he swiftly disarmed. He is strictly devoted to reading, especially reading while walking around the city, and writing. The work itself is pure, he says, engagement with text, application of time and talent to the cultivation of the imagination. He has a circle of writer friends who meet annually in Philadelphia to celebrate Bloomsday. Throop is married to a woman who is at home on the couch maximally pregnant at the start of the book. He think he will skip this year’s Bloomsday, but he changes his mind and kicks off a night of drinks and conversation.

The circle of friends is a mix of writers of varying amounts of career success. Klein draws them individually and successively. He has a lot of talent for this.

Here’s one of Throop’s delightful descriptions of Snare.

I see the kid limp in, one leg not quite as long as the other, this uneven urban kid with a pirate-like facial tic, one eye closed and the other open wide as he yawns the silent barbaric yawp of a newborn… (page 54)

Here’s a later one of the writer Oates:

Oates’s face has some of the satanic innocence of a possessed doll once he gets going but he doesn’t get angry the way Snare does. The possessed doll aspects conceal no meat cleaver. (page 190)

Or here’s Snare getting hit by a car in his youth:

He hadn’t made a decision to step into a street that hadn’t seemed occupied by a car that turned a corner looking left for oncoming traffic as it accelerated to the right and plowed through adolescent Snare, lifting him across the hood god bless instead of pushing him under for the wheels to break what remained unbroken by impact with an American muscle car, its grill like the head of a chrome shark. Somehow he landed on his side and thanks to adrenaline energizing the elasticity of youth pulled himself to the side of the road and there he figured he would die. (page 57)

The writers of the Bloomsday group don’t all show up at the same time, so each member gives Throop an opportunity to talk about aspects of the literary world, such as writing programs, publishers and agents, and the difficulties of landing them, the New Yorker, the traditions of American fiction, the New York Times, the kind of work publishers can sell vs. the kind of work that matters, and the semi-difficult work real writers ought to do.

Klein has spent a lot of time thinking about these things. Like Nabokov, he has strong opinions, but his good nature lets him write a passage like this one below.

The literary world is no larger than the country of Monaco and everyone’s rebelling against their attraction or repulsion to someone within it, something about it, attracted or repulsed by every particular element, but it seems to me the trick involves magnifying and announcing attractions and minimizing or at least restraining repulsions. Anyone can magnify and announce true attraction, but the trick is to magnify and announce minor attraction without undermining integrity.

The trick is to take natural apathy or even antipathy and apply supremely generous perception to it, massage it, roll it between fingers with extreme tenderness like a baby bird with a hammering

startled heart until you find the good in this someone or something you might otherwise have no feelings for or that might even repulse you. (page 96)

The struggles of writing are soul-crushing, so the publishing or notoriety of another writer in your circle can be a catalyst of jealousy and resentment. Klein adds to this possible flammable Bloomsday situation an accelerant in the form of a writer named Jonathan David Grooms who has all the critical and publishing success any writer, even those who’ll never sell out their own integrity, would ever want. He’s young and already in the canon. Grooms is scheduled to join the celebration at the bar when he completes his public reading of the Molly Bloom section of Ulysses at the Rosenbach. Klein dangles this delayed appearance for over 150 pages. I found the wait suspenseful. What would he be like? Would he live up to it? It was like waiting for some demigod to come down from a mountain in fulfillment of an ominous prediction.

When Grooms does arrive, his presence causes the other writers to jockey for a chance to get him to look over their own work. He has the connections that could make a career. Several ask if they can send him manuscripts. Grooms has arrived not long after the writer Gibson has announced he’s quitting writing. Gibson’s reasons are another compelling passage from Klein.

so I figured today I would announce what I’ve known for a while and what I’ve discussed with Casey ad nauseum, she’s literally nauseated by it, sick of the whole discussion that’s taken maybe a year or two from both our lives, which is a really long time to talk about the benefits and drawbacks of quitting writing, and so we’ve decided, Casey and I, that the best thing for me, for us, is to stop talking about quitting writing, never talk about it again, and the only way I can stop obsessive thoughts about quitting writing is to, finally, today, tonight, on this Bloomsday, the only way I can stop thinking and talking about quitting writing is to hereby announce my intention, once and for all and finally and for good, to quit writing so I can stop talking about quitting writing and get on with my life and start talking about something that has some value for anyone other than myself. (page 140)

The announcement sends some shockwaves through the group, but Throop give a strong reply that is based in his own confidence in the work he himself is doing, not the work Gibson is doing. This is what I take to be the heart of the book.

The wave of post-announcement responses flows my way from Snare to England so I clear my throat and enunciate as clearly as possible and raise my voice but don’t necessarily yell, I simply say that’s bullshit, Gibson, total bullshit, especially today of all days, on Bloomsday, our one true holy day. Everyone smiles since I smile as I say it but I’m not sure I’m joking. I’ve reached the point in the night where I speak from both sides of my mouth. (page 141)

Calling bullshit on Gibson’s announcement makes me feel better about my own writing. I do it and I will do it and I won’t stop, it’s not an issue for me, has never been an issue. I’ve never considered quitting writing because it takes time from other aspects of life. It’s not a concern because it’s not a question. Reading and writing are substantial and satisfying on a significant level, to say a religious level doesn’t sound like an exaggeration. The weight of the books on our bookshelves, the beauty of their spines, the pattern of all those rectangular verticals insulating the wall, the weight and beauty and depth of the books, each containing tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of words about life, I can’t imagine not wanting to contribute to that weight and beauty and depth, that heft and truth. I can’t imagine thinking it’s not worth the effort. I can’t imagine thinking I’d be better off doing anything other than writing, than thinking and talking about writing, than reading as a way to talk to writers long gone before me. (page 142-143)

What Throop and Klein are talking about here and throughout the book is a way of life. The jokes and the insults, the arguments and the proclamations of quitting are ways of coping with what can be desperate. There’s a wise Kafka quote Throop pulls up on his phone somewhere in the middle of the book. The impatience he describes is the un-published writer’s despair.

There are two main human sins from which all the others derive: impatience and indolence. It was because of impatience that they were expelled from Paradise, it is because of indolence that they do not return. Yet perhaps there is only one major sin: impatience. Because of impatience they were expelled, because of impatience they do not return.

Like It Matters: An Unpublishable Novel is available now from Sagging Meniscus. You can read more about the book here and where to buy it here:

https://www.saggingmeniscus.com/catalog/like_it_matters/

I strongly recommend you do.

Leave a comment