By Jay Innis Murray

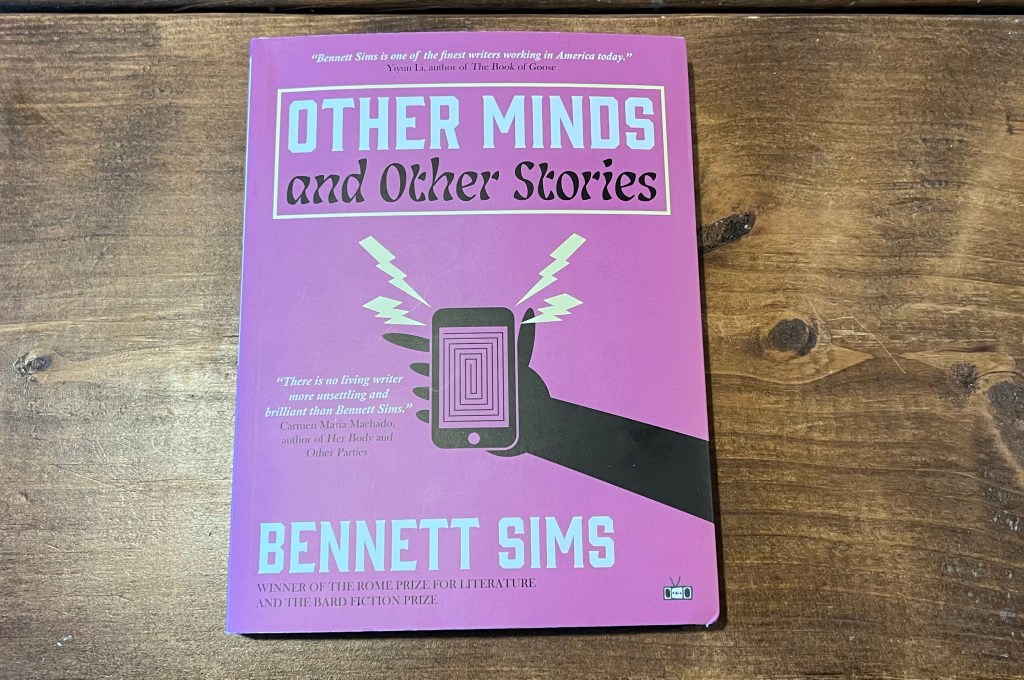

I’m feeling unusually self-conscious as I prepare this appreciation of the new collection of stories from Bennett Sims called Other Minds and Other Stories. See, I’m an underliner. I write in the books I read. I leave, too, significant quantities of margin notes. Some of my book-loving friends have an almost Puritanical revulsion when they see my copies of books. Could they even be friends with a person who does that to a book? How could they understand the mind of a person who does the equivalent of running with cleats across the writer’s future gravesite? Even if this were not my usual habit, I could hardly resist marking up this particular book. Bennett Sims is exacting in his choice of words and making of phrases. One thing about seeing the world estranged through another writer’s mind is that you see the world in a new way, and this new way becomes indispensable to you forever.

Of course, I am referring to the collection’s title story, “Other Minds,” which is about a character called “the reader” who reads on a device like a Kindle and encounters underlined passages that notify the reader how many times other e-readers of the same text have highlighted the passage. The reader does not understand why most of the passages are highlighted. He would not have highlighted them. The narrator states, “He could not imagine what was going on inside these other readers’ minds, while they read.” Although it does not open the volume, this delightful story of only four and a half pages provides a useful way in. We are given something like a map of how or why to read the book. “All his life, if someone had asked him why he read, the reader would have answered that he was curious about other minds. He read to learn how other minds saw, thought, experienced the world. He believed that his own mind could be reflected and enlarged by the language of other minds.” Before we get too comfortable with this notion, we have to remember that the reader, shortly after this in the same paragraph, reveals, “Increasingly the thought of other minds disquieted him.” Disquiet is the mood I take from many of the stories here. By turning the screws of ordinary language, Sims cranks up the uncanniness and delivers some unforgettably disturbing moments.

The book contains twelve stories, and half of these are fewer than ten pages long. The styles and genres are diverse. The opening story “La Mummia di Grottarossa” and the closing story “Medusa” are each a page long, and, as Sims reveals in his Acknowledgements, were written in Rome “in dialogue with” the photographer Sze Tsung Nicholás Leong. They are beautifully thought-provoking thematic bookends for the collection. All the stories are a joy to read. “Unknown” is a story about jealousy that twists with a strange logic. “Pecking Order” is a disturbing tale that reminds me of some of the nightmares of George Saunders. “The Postcard” is a long, dreamy story something like a Paul Auster New York story, but with the soul of Golden Age science fiction.

Occupying something like the center of the physical book is the magnificent “Portonaccio Sarcophagus,” one of the best stories I have read in years. This could be the Sebald fan in me coming to the fore, but this story is a tour de force of the contemporary hybrid form. Like the public lecture chapter in Teju Cole’s recent novel Tremor, Sims’ story is like The Rings of Saturn in that its technique combines a personal narrative with commentary on one or more works of European art. Some black and white images accompany the story and add to the spooky aura around the actual sarcophagus and our front row seat for the narrator’s mind encountering it and fitting it into a pattern of thinking about other cultural objects and tools. A scholarly speculation about the blank face of Pompilius, the tomb’s intended tenant and the subject of the artwork on the sarcophagus (polished by death to a smoothness anterior to life, eroded down to the pale neutral beneath all being) expands to include riffs on the movie The Ring and Google’s Street View tool. We are free to enjoy, as in one of Sebald’s works, guessing or trying to argue whether the personal and family elements of the story come from the life of an IRL person named Bennett Sims.

By the time I got to the end of the single-paragraph story “Medusa” that closes Other Minds and Other Stories, I felt sure this was my book of the year. We’re told: The classical project of literature is to defeat death by fashioning a superior statue. Books are just sculptures that don’t erode: they extend mortal forms across immortal time, preserving impermanent pasts for an infinite future. I believe that’s written sincerely. I can’t do anything other than take it that way. It’s a heck of an ambition.

Leave a comment