By Jay Innis Murray

Enough time goes by, and it is as if old things never happened. Things once fresh, immediate, terrible, receding into old God’s time, like the walkers walking so far along the Killiney Strand that, as you watch them, there is a moment when they are only a black speck, and then they’re gone. Maybe old God’s time longs for the time when it was only time, the stuff of the clockface and the wristwatch. But that didn’t mean it could be summoned back or should be.

– Old God’s Time

Ah no, Jesus, no, lads, not the fecking priests, no.

– same

The Irish novelist Sebastian Barry has been longlisted for the Booker Prize five times. All of these nominations have come in the last 20 years, all since Barry turned 50 years old. With that record of high-status awards visibility, it’s a puzzle to me that I could not easily say how many of my American book-reading friends are among Barry’s readers. Nobody has ever recommended a book of his to me. Old God’s Time is his eleventh novel, so, at 45%, he is shooting a high percentage with the nominators for the Booker. It was published this year by Faber & Faber and Viking in the US. Although it was not selected for the shortlist, it could easily have been. It is an effortlessly graceful novel that shows off Barry’s storytelling gifts.

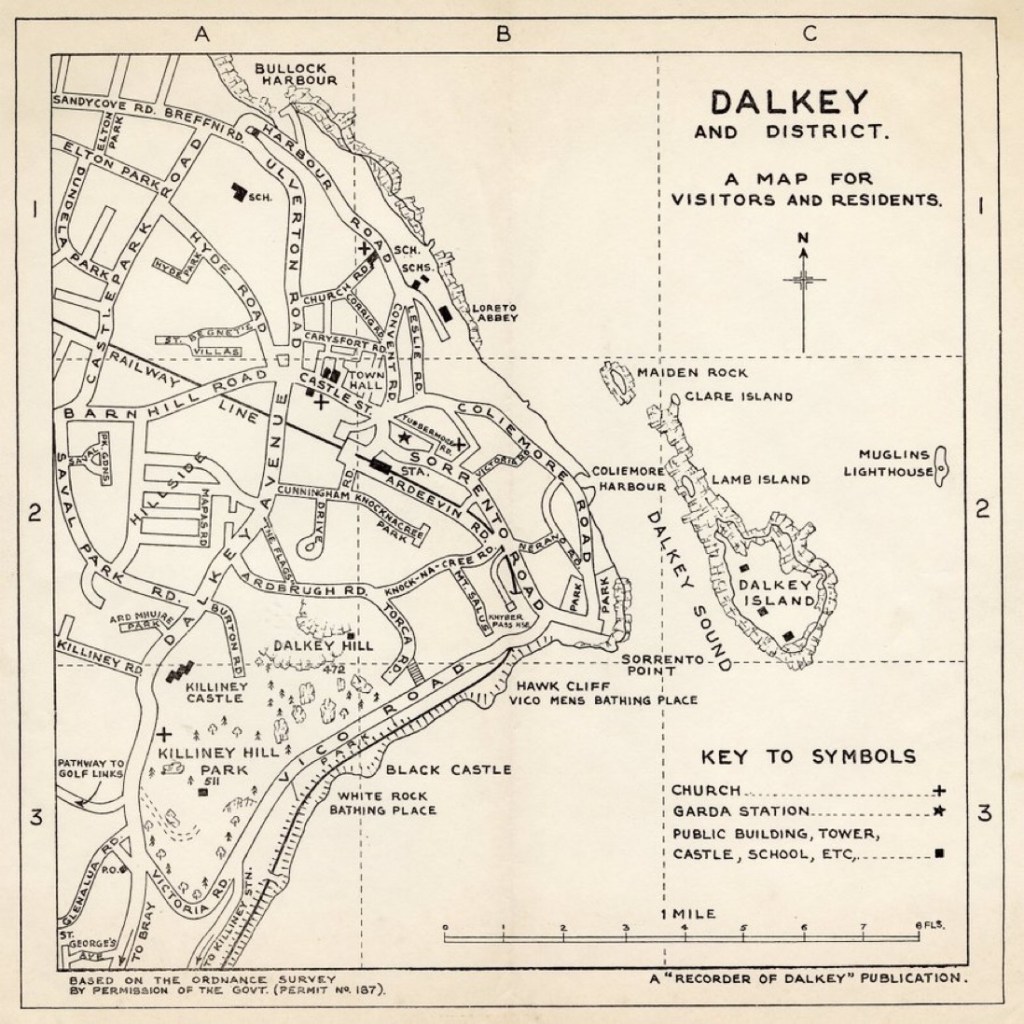

Old God’s Time is the story of Tom Kettle, a police detective sergeant who has settled into a quiet existence on the coast of Dalkey, nine months into his retirement. The present day of the novel is the middle of the 1990s, so that when the narrative reaches back into Tom’s memories to tell his life story, many of the events revive a more turbulent time in Irish history. As in many stories of retired cops, Tom Kettle is self-conscious about the change in his lifestyle. That’s not to say he is unhappy about it. “Stationary, happy and useless,” he says of retirement. When he’s visited by two younger police detectives at the start of the novel, he knows how he must look, but he’s not alarmed. “He is aware now of his slippers. Perhaps he might have put on his shoes before he opened the door—it had not occurred to him. He must look a bit defunct presenting himself thus.” Defunct is a perfect choice here. The retired man, especially the retired police man, a tool of the state, is a defunct piece of technology. He’s no longer in use. “Retired men are to go to the devil—into the final dark, let the waters close over their heads—unless they have curious gifts,” the narrator has Tom think. “Rare gifts. He hoped it was so.”

Tom chooses words carefully. Like a philosopher, he doesn’t like statements he can’t back up. His creator has let on that he built him this way with a purpose. In an interview, Barry said, “My prayer was that, by being forensic in my descriptions, when necessary, readers might elect to take on some of those images and memories, as an act of solidarity – a witchy magic, an act of sympathetic empathy.” It is Barry’s style that casts the witchy spell, his novelist’s skill in pleasing us with layers of detail. Led that way, the act of empathy comes easy. This is important to keep in mind since this book has a dark heart.

The style of the language in Old God’s Time is light and clear. The narrator has a cop’s eye for noticing. The voice will soar to poetic registers, often in joy at the scene in Dalkey and his eccentric neighbors, and it smoothly downshifts to short, declarative sentences, in the mode of a crime novel, when Tom Kettle’s mind sets on the personal and professional history that troubles him. In either gear, the prose is transparent in the best way, which is hardly what you could say about the structure, the author’s habit of embroidering the rug he plans to pull out from under you.

We learn early on that Tom Kettle is haunted. He sees people, young children, running by the sea or dancing on the grass in his landlord’s garden. They could be real. They might be ghosts. They might be figments. When he asks about them, he’s told things that seem impossible. Just over 30 pages into the novel, Tom says something about his own family—his son, Joe, and his daughter, Winnie—that contradicts other facts we’ve been told. If there is a scale of fallibility in a narrator that runs from the unimpeachable all the way to something like Satan’s empty promises, Tom Kettle sits in a border zone. There are signs. We keep our guard up. Barry defends his man in a charming way when he says, “I felt my job was to be his witness and to see and hear what he was seeing and hearing, and to take it down faithfully, and not butt in.”

The shape of the novel is, roughly-speaking, a non-linear telling of Tom Kettle’s life—a tale that piles up with unearned pains like Job’s—intertwined with Tom’s slowly boiling involvement with a cold case brought to him by the two young police colleagues mentioned above. A cold case is a fictional device that can only drag an ex-cop into the past. It doesn’t matter if he wants to go. It’s inevitable. The time has come. As Tom says, “The main drone of the pipes he heard under everything for sixty years and more was alarm and confusion, like the very pith of battle.” Call it PTSD. This particular cold case will show him brave in facing it.

The dates of some of the events in the novel require some puzzling out from clues. Tom Kettle was born in 1930. He’s an orphan, and until age 17 he lives in a home for orphans with the Christian Brothers. He calls those years of his youth “the empire of the Irish priesthood.” He is beaten for wetting the bed. Other things that did not happen to him, he witnesses happening to others. “He had seen it with his own eyes, the boys the Brothers were raping, with the light in their eyes put out. Boys put to the sword of their lust. He had seen it. He had witnessed it when he didn’t even know the words for it, when he couldn’t have described to anyone what he had seen. The little wicks of their eyes put out.”

It’s an era in Tom’s life and an era for Ireland. “The best things in Ireland were the work of unknown hands,” we’re told, “And oftentimes the worst crimes.” Like in the United States, an Irish archbishop had the power to cover up vicious crimes as if they’d never happened. Tom is able to leave the Brothers when he is 17 and joins the British army. He follows the Empire, first to the Middle East, but when the British leave Palestine at the end of 1947, Tom is shipped to Malaya. There, he develops an uncommon skill with his rifle. As a sniper, he kills 57 people during the Malay rebellion. “He was a murderer of course. He had killed many times. The butt of his rifle was notched with fifty-seven knife marks.” He’ll be able to muster up this skill in his old age, at the very end of the novel, when life depends upon it. The skill also gets him a job in the police when he comes home to Ireland.

As a young detective, he meets June, an even younger waitress who will become his wife. June has been dead for ten years in the present time of the novel. Many of the ecstatic stretches in the novel, as well as the most melancholy laments, are about June, Tom’s premature loss of June, and his June-less life that goes on despite his indifference to it going on. I’ll quote now from the passage leading to the first time the couple has sex. It is some of Barry at his best.

And one lazy Saturday on her day off they sat in a bar in Blackrock and lent half an ear to some ould match on the radio, and drank cider, feeling like a king and queen of the world, and walked all the way past the Carnegie Library, and the posh Volkswagen garage, and along the high road built along what must have once been a wild coast of cliffs and rocks, where ships no doubt came to grief, tamed only by the racketing railroad, and the enormous mansions that fronted the way, the salt wind attacking their facades. And they walked hand in hand all the way along the tremendous seafront of Monkstown, the little bodies of people below shivering on their towels, or braving the wretchedness of the Irish Sea, and they went down a little way past the big iron gates of the hotel, and past the tennis club lurking in its cowl of woodland, and crossed the iron bridge, their shoes going clack-clack-clack, and got out onto the old sea-field at Seapoint, luxuriant with the August grass, tall and shedding its seeds, and they found a discreet hollow like thousands of lovers before them, and hoped no boys would be nearby and lob rocks at them, and kissed like crazy kids themselves, falling deeper and deeper into the bottomless pool of love, and made love like moaning demons, and if they didn’t make Winnie that day, he was a Dutchman.

Poor, beautiful, doomed June has known the same youth as Tom, under the empire of the Irish priesthood. Except much worse. During their honeymoon, she reveals to him what she’d only hinted at during their courtship, a truth he suspected and that she waited years to share from fear he’d change once she told him. She’d been raped repeatedly by a priest named Father Thaddeus. Barry carefully and tenderly describes their conversations. Time passes. They raise a daughter and a son together. Tom praises her skills as a mother. His love only deepens. Tom lives through serious work traumas. He wins a medal after stepping in front of a bullet to save a woman. In a tour de force, Barry writes about Tom’s stumbling upon the scenes of the May 1974 Dublin car bombings. As a couple they seem to survive everything. Everything except the return to visibility of Father Thaddeus and the immoral, institutional burial of his crimes.

The cold case involves the death of Father Thaddeus. Barry builds a great thriller tension around this and Tom’s (and June’s) possible involvement in it. As readers, our sense of Tom’s sense of reality is not stable. We encounter contradictions of prior claims, denials of previously established facts, alternate timelines, implausible physical acts, past times superimposed over the narrative present, even an entire scene in a police station that Tom dreams while sitting on a bench in St. Stephen’s Green. This is all quite fun in the hands of an artist. The last stretch of the book does punch hard, as a few things we hoped were unreliable tall tales that would be corrected, like a Monopoly bank error in our favor, turn out to be, sadly, true. Barry pulls the rug right out from under our feet. Tom’s life does resemble Job’s, a serious test of faith, but it is a faith in life not in God.

Leave a comment