By Jay Innis Murray

Many contemporary critics fail to understand that the term autofiction suggests slipperiness, an estrangement of the I-narrator, who may or may not have the same name as the author, so that the space of the work can become a space of freedom.

– Kate Zambreno

WG Sebald insisted his narrative works were prose rather than novels, a distinction that makes sense except to the marketers of books who have the instincts of taxidermists. I believe in the claim of a space of freedom. The Zambreno quote comes from her book To Write as if Already Dead, published a year after her autofictional Drifts, which has the words a novel on its cover. To Write as if Already Dead is more of a true hybrid than Drifts and covers some of the same subject matter. It combines a compelling novella (its first half) with a thrilling close reading of the life of Hervé Guibert and his book To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. The freedom on display in the form, the connected subject matter and the style made it resonate and succeed for me in ways Drifts did not consistently achieve.

Teju Cole’s new novel Tremor is likewise stirring in its strangeness and wide range. As it explores problems of 21st century storytelling (“How is one to live,” the character Tunde asks, “in a way that does not cannibalize the lives of others, that does not reduce them to mascots, objects of fascination, mere terms in the logic of a dominant culture?”) and offers some solutions to these problems, it also highlights the type of book that can simultaneously compete with straight-up realist novels, history books, essays, podcasts, and social media like tweets and TikTok videos. How much do you trust a fragmentary structure? As Donald Barthelme wrote, fragments are among the only forms I trust.

The book opens in territory familiar to readers of Cole’s previous fiction. Third-person narration introduces a character like Open City’s Julius who is a Nigerian American living in a northeastern US city. Here, the city is Cambridge, MA in greater Boston, the environs of Harvard University. We follow his activities for several pages before we learn his name is Tunde. Like the real-life person Teju Cole, he is a professor and photographer. In the way that Julius has a Sebaldian interest in the history of New York, Tunde looks closely at the colonial history of Massachusetts and the traces of the history of slavery that can be seen around him. An aura of threat hangs over the opening paragraph, and thus over Tunde’s first act in the chronology of the book. He tries to capture a photograph of a hedge he has wanted to photograph for a while.

THE LEAVES ARE GLOSSY AND dark and from the dying blooms rises a fragrance that might be jasmine. He sets up the tripod and begins to focus the camera. He has pressed the shutter twice when an aggressive voice calls out from the house on the right. This isn’t the first time this kind of thing has happened to him but still he is startled. He takes on a friendly tone and says he is an artist, just photographing a hedge. You can’t do that here, the voice says, this is private property. The muscles of his back are tense. He folds the tripod, stows the camera in its bag, and walks away.

The narrator does not dwell on the interaction. The story immediately moves on to another episode, but the unease hangs over Tunde for the sections of the book that are set in the United States. There is the threat of aggression and violence everywhere. Past and future violence. Details of Tunde’s personal life are somewhat sparse, but there is a separation, what Tunde calls a “brief separation” with its implication of return and repair, between himself and his wife Sadako. Although marriage and family life are not the focus of the book, they are part of the unsteady ground, contributing to the tremors underfoot.

There are two truly accomplished sections of this book that I wish to highlight. As Teju Cole assembles Tremor from experiences, pieces of scholarship, and meditations on the ethical implications of his role as the assembler, he makes a strong claim in defense of this hybrid poetics. By implication, it approves and defends the freedom of autofiction.

The Lecture

The fifth chapter of Tremor comes in the form of a public talk at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It occurs a bit over a third of the way into the novel. There is no framing of the text. It opens with: Are we recording now? Yes? OK. Due to the lecture form, this chapter is not given in third-person narration. The speaker uses “I” many times, as you would expect, and, for all I know, this could be the insertion of a real talk in the real museum by the real Teju Cole. It is a tour de force of public education and, I’d add, searching accusation.

The speaker begins his talk with JMW Turner’s painting The Slave Ship, which is on display at the museum. He writes:

Depending on which of the entrances I’m using I either see it in the distance or suddenly to my left and only on seeing it do I remember: this is here. The painting grabs hold of me in an unpleasant way. I’m talking about J. M. W. Turner’s Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On). No encounter with this painting can be pleasant. Its details are terrible and its full title directs our looking, telling us to focus first on the grisly foreground and then on the roiling weather in the background.

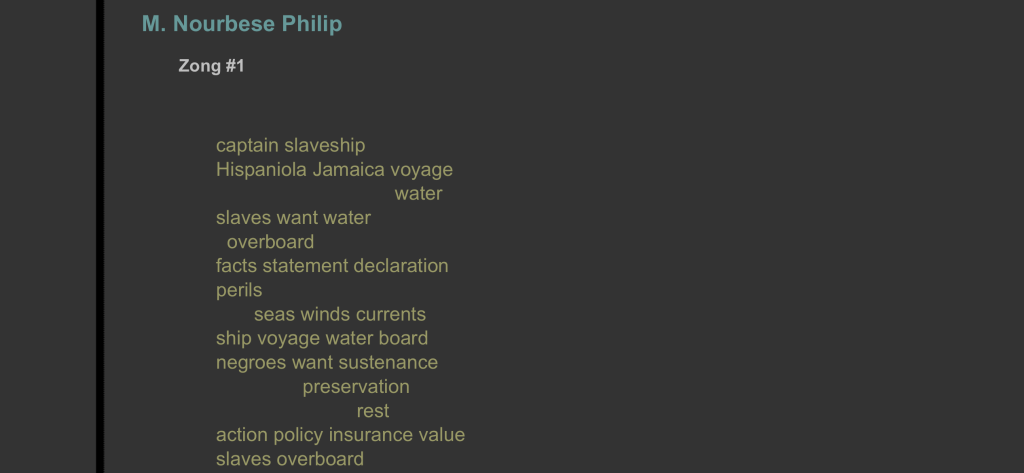

The speaker discusses the troubling title of the painting (and the way the word slave itself “strikes the ear like a lash”), the completion by Turner of the painting and his sources for it, Ruskin’s praise for the painting, which contributed to its fame, Turner’s technical limitations, and finally, before changing subjects to another painting, the comparison to a book-length poem called Zong! by Marlene NourbeSe Philip, which is about the same subject, the same slave ship, the legal case around it, the horrendous, dehumanizing legal language, “a story which cannot be told,” which Philip manages to tell. The speaker says:

Philip wails out the lives of the people massacred on the Zong. Like Turner she paints a picture of a creaking ship beset by heaving waves. But out of that ragged material she has made something far more personal and holy. We get a sense of actual persons destroyed. We are spattered by history’s bitter spray. It is not the spectacle of loss that Philip foregrounds but rather the interwoven hurt of these people, not impossible limbs as painted by Turner but possible lives taken from people for whom, in the absence of records, she has conjured credible names: Muru, Kakra, Kolawole, Kibibi, Olabisi, Usi, Kenyatta, Mesi, Nayo, Yooku, Ngena, Wale, Sade, Ade.

The contrast between the ways of making art about the same history returns us to Tunde’s concerns I quoted above. How is one to live in a way that does not cannibalize the lives of others, that does not reduce them to mascots, objects of fascination, mere terms in the logic of a dominant culture? Turner’s painting fails this ethical test, born as it is deep in the logic of the dominant culture of 1840. Philip’s poem does not fail. It is holy.

The Voices from Lagos

The lecture gives an ethical grounding for what will be received as the most important chapter in Tremor. It comes immediately after the lecture. The reader has been primed and should be alert to ask if we witness a trespass in Chapter Six. Do we sense anything like identity theft since what comes are 24 distinct voices, nothing less than a tapestry of social life in present day Lagos? Again there is no framing for these texts. They are short, fragmentary, first-person accounts, as if somebody is changing from station to station on a radio of oral histories. They depart entirely from Tunde’s presence in the third-person storytelling and his or Cole’s voice in the museum lecture.

The experiences written here (and regardless of the arguably ethical superiority of oral history, this is writing) include the experience of waiting in line for water or wasting time in Lagos traffic. Family battles over inheritance. Fraud in the contracting business. The illness and death of a child. Living through an armed home invasion. Women selling cloth (You can’t fool a Nigerian woman when it comes to cloth). The account of a mudslide below the homes of the rich that kills a poor child. Bullying. A man testing out his own coffin. Church music. A painter of murals under bridges. (It doesn’t matter how the image is erased, whether by rain or by human hands, whether by nature or by culture. What matters is that I was there, that I spent those hours, that it was there, that it existed and flourished for however long it did). In a sort of summing up, a woman who works in radio says, The people who call in are not calling to talk to me. What do they really know of me? They are calling to be heard and to hear a sympathetic voice. All they know of me is my voice.

Throughout this long chapter, we get a sense of actual persons, and of social life in a megalopolis. Tremor is an important book. It moves Cole out of the shadow of his predecessor Sebald, and it moves with a freedom of form that will contribute to our future discussions of the successes of autofiction. The novel is nowhere near an exhausted mode.

Leave a comment