By Jay Innis Murray

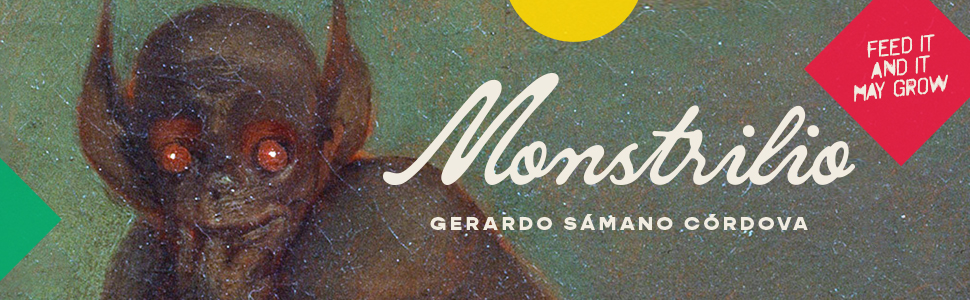

Monstrilio from Zando, published March 7, 2023

One of the joys of this literary horror novel is the deft and seemingly effortless way author Gerardo Sámano Córdova manages a sort of thimblerig of relationships and points of view. I don’t mean his concern as a writer is to fool the reader. Rather, the shell game is the best visual transfer I can offer of the shifting of relations in the book. Let me introduce the plot.

Magos and Joseph are a married couple living between New York and Mexico City whose only son Santiago is born with just one lung. He lives into adolescence (after it was not expected he’d survive infancy), but when he does pass away at age 11, his mother Magos cuts out a piece of his lung from inside his dead body, puts it in a jam jar Santiago used to keep his pencils in and cultivates and grows it like it’s a plant or some kind of microorganism. This happens at the open of the novel. The description of her act is beautifully haunting. It’s uncanny in that the act is accepted by her husband and best friend Lena, and Magos is not turned in to authorities nor swarmed by police or psychiatric professionals. The world of Monstrilio is one in which such things happen. It’s our world, but that world tinted by that twilight that comes between day and night. That time when night has not fully taken over. Such acts are rationalized, not by argument, but by an acceptance that feels around like an insect with its antennae and that pulls all of the characters into its embrace. The engine of the story’s plot comes from the fact that the lung begins to develop, first into a small, furry, blood-thirsty monster and, later, into a young man, Monstrilio who might not be Santiago but who has his memories.

The book is divided into 4 sections, each with the POV of a major character. In order, these are Magos, Lena (Magos’ best friend who is probably in love with her), Joseph, and M (for Monstrilio). The motions of the shell game I mention above are structured around the shifting disagreements about what to do with Monstrilio as he develops, first as a monster, and then as a man who struggles to control his monstrous nature. Magos and Joseph disagree about what sorts of freedoms to give M. Magos and her mother (and her mother’s housekeeper) fight about M’s very right to be alive. Magos and Lena argue over how to care for M and his injuries and appetites. They later swap sides of the fight. Joseph and Magos change places often throughout the book as M’s primary caregiver. How that becomes a tool in the hands of the author who gives us 4 distinct points of view is a sign of great promise in this young writer.

Monstrilio in the world is a problem. In the forms of both monster and man, he likes to eat raw meat and live animals. He likes to bite. He sometimes likes to bite people, and, driven to blood lust by the animal smell of a human (and the sometimes consensual sexual biting he gets involved in), he might, even in his mature human form, devour a living person. Like the monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, when he’s free in the world, there is no telling what Monstrilio might do. There is in fact quite a bit of Frankenstein in this novel.

In the section she narrates, Lena (who is a medical doctor), says:

I looked for creatures that resembled the monster on the internet or documented cases of people turning organs into independent organisms, but apart from fantasy and lore, there was nothing. I wished I could’ve examined the creature, determined what it was and where it had come from. What if it was Santiago’s lung? Wouldn’t that have been a groundbreaking discovery, someone bringing a creature to life solely with their own grief and a prodigious unwillingness to let go?

In her section, Leda also provides descriptive witness to the monster’s ongoing transformations:

Magos said [the monster] was developing, that it wasn’t as round anymore and would soon stand upright. I wasn’t sure it would stand upright, but it was getting bigger and was growing four stumps that resembled paws, or possibly hands and feet. At times, Monstrilio stretched wormlike and stared at its new extremities. It bit at them. Magos began referring to Monstrilio as he. Monstrilio wasn’t Santiago, but he was becoming his own being, the ties that bound him to Magos’s pain thinning, his original darkness giving way to something new and independent.

The style of Monstrilio is generally tender, kind, and warm. That may be strange for a horror novel, and some of the scenes are horrifying and bloody, but it is effective since this book is ultimately about familial relationships, nurturing the innocent, and grief. Every speaker in the novel circles back to memories of Santiago, the lost son.

Here is Joseph (father of Santiago and Monstrilio) in his section:

When Santiago was alive, I used to have visions of what he would become. Not visions like mystical forebodings; more like wishes. In these he would be thirty, my age back then, and I’d be old, older than math and logic would account for. I would be sitting at the head of a great picnic table with Magos and Santiago by my side. Lena would be there and Uncle too. Though, again, math and logic couldn’t account for how he would still be alive. Also, other shapeless friends and well-wishers. We’d sit under the shade of a humongous tree, most likely at Firgesan but not conclusively. Santiago spoke at the event, which alternated from birthday to anniversary to unprompted celebration. “Best dad,” he would say, and he’d tell our dear ones how they only knew one part of me, how he was lucky to know all of me. I’d cry imagining this because, beyond all of the self-indulgent details of this moment, Santiago was alive and happy. It was an amorphous happiness because I wasn’t able to imagine the specifics of what made him happy, but he was happy.

The final section of the book is M’s own section. It’s the best. The strangest prose is here since the end of the story is told by a person who has transformed from monster into human, and his changes may not yet be done. This human form isn’t a final stop. We learn about the life he’s made for himself. He has a job in a bookstore. He answers Tinder-like ads from men who are interested in being bitten or even eaten by another man. He deals with the memories he’s inherited from Santiago. They are ad vivid and sensual as if he’d experienced them.

I take out dirty plates to the sink. A sliver of pink sunset light shines on the wall in front of me. So pretty a dread grows right in my chest. Monstrilio loved this light the best. Night is when we’re hungriest. And hunger can be magnificent. I stare at the half-washed dishes. I fight to push the dread out. I pretend my time as Monstrilio is hazy. Muffled sounds and blurred colors. I say I remember warmth. But I don’t say I miss my fur. I don’t say I’m hungry because my hunger is what make everyone scared. They are happy to believe I forget how they maimed me.

The burrowing into the possible subtexts of this book belong to a different sort of essay. That last line above suggests a lot of the tunnels you can find underneath. Sure, his monster body was maimed when his strange arm tail was surgically removed. This accelerated his becoming. But we’ve all been maimed. The shells move fast. The pea is you. It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Leave a comment