“Just another epiphany. Art triumphs once again.”

There is a strange absence of menace in David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future (2022). My personal alarms go off any time a sharp thing cuts or threatens to cut human flesh. I can’t bear to watch the scene when Jack Nicholson gets his nose sliced in Chinatown. Nearly all of the cutting in Crimes of the Future, though, is done unto the willing. We’re told, too, pain has evolved away for certain humans in this future. What I’m trying to get at here in claiming the absence of menace is the apparent flatness of the hierarchy of conspiracy. When we get the suggestion of a second layer from the agents Router and Berst, the tone is decidedly chill. What is the feel of this future?

Is there a world outside the seaside town that is the setting? Are there people? After the grand shot of the cruise ship on its side in the film’s cinematic opening, the rusting, beached ships have the look of stage sets. Same goes for the abandoned, stone tower Tenser and Caprice live in.

Rusted ships like stage sets.

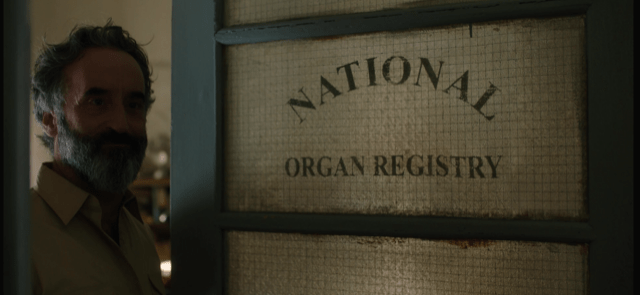

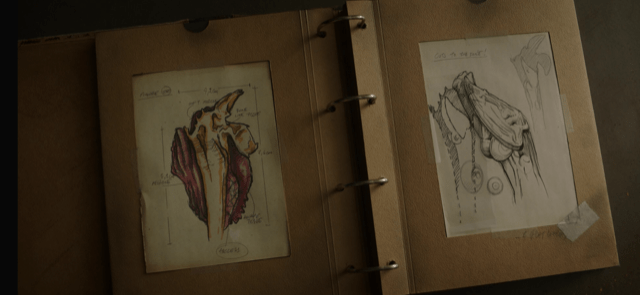

The National Organ Registry with its door like a noir detective’s office gives this future the vibe of decades past. Drab and colorless. The records kept there are thick paper folders bound shut with elastics and string. The office walls are crumbling, undecorated. The example of a record shown is more like a scrapbook than a medical or governmental file.

Just how national is this organization?

Records like scrapbooks. A comment on fandom perhaps.

Shelves of paper records.

The two employees of the Organ Registry have moved in and established an office, but is there a larger organization out there? Even clandestinely, does it exist?

Same with the police. The detective or operative we meet is Cope. He’s a solo act. There are no other police. He does not report to a superior in any scene. He never realistically threatens to arrest anyone.

Cope in the blank interrogation room.

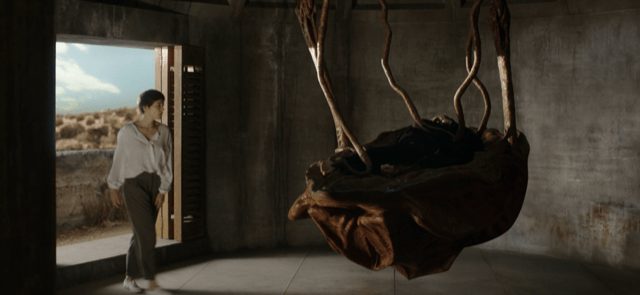

Lastly, there is the tech. As in prior Cronenberg films like eXistenZ, the tech looks like it is made of organic material. It’s skeletal. Limbs of the machines that interact with Tenser’s body look like bones. He sleeps in a strange bed that looks like half of a walnut suspended from the ceiling by thick connectors like vines or elephant trunks. The weird found-half-buried-on-the-ground qualities of their forms contrast with the biomorphological coordination of their functions. They seem to work. Technicians come and recalibrate them, and they work better. It’s so dreamy.

“I think this bed needs new software. It’s not anticipating my pain anymore.”

The casual jargon all sounds to irrelevant to the empty, abandoned world, but perhaps that emptiness is an illusion. “Just another epiphany. Art triumphs once again.”

Leave a comment