By Jay Innis Murray

In his lecture on Proust, Nabokov breaks down what he considers three especially distinctive elements of Proust’s style. With a flourish of humor, he describes metaphorical imagery, clauses, and Proust’s merging of conversations and descriptions. As a prelude to this, Nabokov makes a claim about style in general. It’s not a controversial statement.

Style, I remind you, is the manner of an author, the particular manner that sets him apart from any other author. If I select for you three passages from three different authors whose works you know—if I select them in such a way that nothing in their subject matter affords any clue, and if then you cry out with delightful assurance: “That’s Gogol, that’s Stevenson, and by golly that’s Proust”—you are basing your choice on striking differences in style.

The stuff of pop quizzes, chalkboards and lecture halls. I was thinking of this when I encountered two passages that maybe could be put to this test.

Entry Number 1

She thrust [the letter] behind her back; I put my arms round her neck, raising the plaits of hair which she wore over her shoulders, either because she was still of an age for that or because her mother chose to make her look a child for a little longer so that she herself might still seem young; and we wrestled, locked together. I tried to pull her towards me, she resisted; her cheeks, inflamed by the effort, were as red and round as two cherries; she laughed as though I were tickling her; I held her gripped between my legs like a young tree which I was trying to climb; and, in the middle of my gymnastics, when I was already out of breath with the muscular exercise and the heat of the game, I felt, as it were a few drops of sweat wrung from me by the effort, my pleasure express itself in a form which I could not even pause for a moment to analyze; immediately I snatched the letter from her. Whereupon [she] said, good-naturedly: “You know, if you like, we might go on wrestling for a little.”

Entry Number 2

My heart beat like a drum as she sat down, cool skirt ballooning, subsiding, on the sofa next to me, and played with her glossy fruit. She tossed it up into the sun-dusted air, and caught it–it made a cupped polished plop. [I] intercepted the apple.

“Give it back,” – she pleaded, showing the marbled flush of her palms. I produced Delicious. She grasped it and bit into it, and my heart was like snow under thin crimson skin, and with the monkeyish nimbleness that was so typical of that [type of creature], she snatched out of my abstract grip the magazine I had opened (pity no film had recorded the curious pattern, the monogrammic linkage of our simultaneous or overlapping moves). Rapidly, hardly hampered by the disfigured apple she held, [she] flipped violently through the pages in search of something she wished [me] to see. Found it at last. I faked interest by bringing my head so close that her hair touched my temple and her arm brushed my cheek as she wiped her lips with her wrist. Because of the burnished mist through which I peered at the picture, I was slow in reacting to it, and her bare knees rubbed and knocked impatiently against each other. Dimly there came into view: a surrealist painter relaxing, supine, on a beach, and near him, likewise supine, a plaster replica of the Venus di Milo, half-buried in sand. Picture of the Week, said the legend. I whisked the whole obscene thing away. Next moment, in a sham effort to retrieve it, she was all over me. Caught her by her thin knobby wrist. The magazine escaped to the floor like a flustered fowl. She twisted herself free, recoiled, and lay back in the right-hand corner of the davenport. Then, with perfect simplicity, the impudent child extended her legs across my lap.

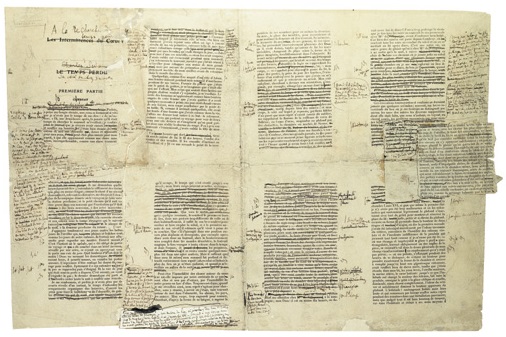

Can you pass the quiz? It strikes me that Nabokov had entry Number 1 from À la recherche (Within a Budding Grove) very much on his mind when he wrote Entry Number 2, which is obviously from Lolita.

The two passages share several elements. The scenario is identical (wrestle over contested object). The descriptive style has all the heat of two bodies in contact as each narrator conveys what the reader recognizes as the unprecedentedness of the event. Outside the text I pulled, just after, there is an identical resolution of tension (ejaculation without consummation). I don’t feel that Entry Number 2 can be mistaken for Proust, but Entry Number 1 reads strikingly like Nabokov could have written it. Every writer creates his own precursors, Borges wrote of Kafka. Even the greatest.

Leave a comment